Chris Cheung

The Neurobiology of Mindfulness: 5 Key Areas

It may seem simple; we focus on our breath, or on body sensations or even our thoughts, but there is a whole neurobiological dynamism taking place as we explore the different aspects of the practice.

Chris Cheung, www.atoolkitforlife.com Tweet

The practice of mindfulness is an active one. As we look ‘under the hood’ of what is happening we begin to get a real appreciation for the complexity of our minds. The practice is simple; we focus on our breath, body sensations and thoughts, but there is a whole neurobiological dynamism taking place as we explore the different aspects of the practice.

Research on the neurobiology of mindfulness is young. But, having a simple understanding can be beneficial. This understanding underlines the potential to transform on a ‘neurobiological’ basis; to restructure the way our neurobiological systems respond. It also drives home that the practice can be deepened.

What follows is a guide to what is happening when we practice mindfulness – highlighting five key neurobiological areas involved in mindfulness practice.

Neurobiological resulting from mindfulness practice can be observed during or just after practice are the following; many changes can be observed after just 20 minutes of practice.

Chris Cheung, www.atoolkitforlife.com Tweet

During Meditation and just after

The neurobiological changes that can be observed during or just after practice are the following; many changes can be observed after just 20 minutes of practice.

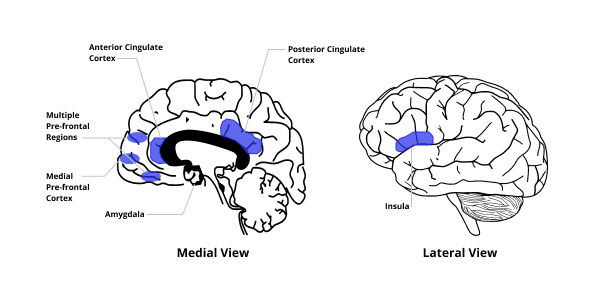

1. Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC)

Mindfulness practice increases activity in the Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC) reflecting an increase in attention. [1, 2]

The ACC, located deep inside the forehead, behind the brain’s frontal lobes, is the region associated with attention in which changes in activity and/or structure in response to mindfulness meditation are most consistently reported. [3] It is also associated with self-regulation, meaning the ability to purposefully direct attention and behavior, suppress inappropriate knee-jerk responses, and switch strategies flexibly.

2. The ACC Junction

The ACC has connections with both the “emotional” limbic system and the “cognitive” prefrontal cortex. The ACC is therefore seen to have an important role in integration of neuronal circuitry for self-regulation. When we are stressed both the ACC and the PFC are deactivated reflecting an inability to control thoughts, emotions, anxieties.[4]

On the other hand the greater the connectivity between the ACC and amygdala the greater the stress. The amygdala is a very old part of the brain which processes fear, negative emotions and emotions in general. Mindfulness meditation reduces stress by decoupling this connectivity.[3]

3. Posterior Cingulate Cortex

The posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) is associated with mind wandering. This area is activated during stressful periods where there is more ruminating and self-referential thought. Mindfulness practice leads to a decrease in activity in the PCC reflecting a reduction in anxiety.[4]

4. The Prefrontal Cortex – frontal limbic networks

During mindfulness practice there is increased activity in the fronto-limbic networks. As these areas become increasingly engaged it has been shown that this improves emotion regulation and reduces stress.[1][2] Research also shows that increased activation of the ventrolateral PFC can regulate emotion by decreasing the activity of the amygdala.[5]

The prefrontal cortex lies at the very front of the brain and makes up over 10% of its volume. It is said to be involved in many functions and is particularly known for executive function. Executive function includes a range of cognitive processes including planning, decision-making, problem-solving, self-control, and acting with long-term goals in mind.[6]

5. Insula

When practicing mindfulness the blood flow in the mid-frontal lobe and insula increase.[7] This area of the brain is connected with intraception – feeling what’s happening inside – and research shows that the increased activity in this area leads to greater sensitivity to things like gut feeling and transient body sensations.[8][9]

The word insula comes from the Latin word for ‘island’. It is a small region of the cerebral cortex located deep within the lateral sulcus. It is an area of the brain which has not been researched that much up until recently. [10]

Long Term effects

Beyond the actual moment of the practice, mindfulness practice can also produce longer term structural changes to the brain. These include:

- Improvements in white matter connectivity in anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and PCC which are correlated with enhanced positive emotion and decreased stressed, indicating an overall improvement in psychological well-being.[11]

- Less decrease in both grey matter volume and attentional performance with age.[12]

- Reduced activity in the default mode network indicating that long-term meditators are able to self-regulate better.[12]

- Reduced basal stress level of cortisol and increased basal immune function, suggesting better health outcomes.[13]

- Enhancement to activity in brain areas related to intraception and attention such as the PFC, the right anterior insula and the right hippocampus. These areas are related to attention and visceral awareness.[14, 15]

As neurological technology advances we will begin to understand more the distinct components of mindfulness meditation such as focused attention, open monitoring (nonjudgmental moment-to-moment observation of one’s experience), and loving-kindness compassion practice and their specific physiological outcomes.

Chris Cheung, www.atoolkitforlife.com Tweet

Still a lot to learn

There is still a lot that we do not know on the neurobiological affects of mindfulness practice. Different practices, for example, may have different affects; mindfulness meditation more than concentrative forms of meditation (e.g. focusing on a mantra) has been shown to stimulate the middle prefrontal brain associated with both self-observation and metacognition and foster specific attentional mechanisms.[16] As neurological technology advances we will begin to understand more the distinct components of mindfulness meditation such as focused attention, open monitoring (nonjudgmental moment-to-moment observation of one’s experience), and loving-kindness compassion practice and their specific physiological outcomes.[16]

Not bad for a day’s sitting

There’s a great deal happening ‘under the hood’; as we practice mindfulness some areas – such as the ACC and the PFC – become more active as our capacity for attention grows and as we begin to regulate our emotions. We also become more self-aware through the activation of the insula. Other areas such as the amygdala and PCC become less active reducing our feelings of anxiety and stress and our tendency to mind wander.

The great thing of course, is that the more we practice, the more the structure of our brain changes, the more it becomes a part of our everyday life.

All in all, not bad for a practice which can take less than 20 minutes a day.

More to explore

Mindfulness Breathing Space: The Pleasant

So, they say we have a tendency to turn towards the negative. A natural consequence of our need to survive.

Mindfulness Check-in to Boost Your Mood

During the holiday seasons there can be feelings that you ‘should’ be feeling one way or the other way; because it is a holiday perhaps

Mindfulness and the Dark Side of Social Media

On the one hand social media has many positives; it can connect us and provide us with digital communities. On the other (dark side) it

How to Find Your Passion: 5 Mindful Insights

So, how do you find your passion? A question that I’ve been asked and that I have asked myself quite often. The question has a

References

- www.nature.com/articles/nrn3916

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mechanisms_of_mindfulness_meditation

- A systematic review of neurobiological and clinical features of mindfulness meditations, 2010, A. Chiesa* and A. Serretti

- hbr.org/2015/01/mindfulness-can-literally-change-your-brain

- What Are the Benefits of Mindfulness? A Practice Review of Psychotherapy-Related Research, Psychotherapy Theory Research Practice Training · June 2011

- neuroscientificallychallenged.com/posts/know-your-brain-prefrontal-cortex

- www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00212/full

- www.youtube.com/watch?v=aPlG_w40qOE

- www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-26268-w

- www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/insula-en

- www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2932577/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17655980/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23696104/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S030439400700451X

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prefrontal_cortex

- https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/features/pst-48-2-198.pd